The Hungarian Government has identified its new target: Index.hu, the country’s biggest independent news website, is now under the indirect control of government-friendly investors. Their journalists, in the meantime, have promised that they won’t give up without a fight.

“They have a baseball bat, but we took out a chainsaw,” said Zoltán Szabó, content development officer of Index.hu, in an interview with the media industry website Kreativ.hu, in which he explained how the government is trying to meddle with their newsroom and how he and his team are fighting back. In the interview, Szabó and editor-in-chief Attila Tóth-Szenesi acknowledge that while the future of the news site has indeed become uncertain, they still find it possible to maintain their independence in the current situation and will continue doing their job as long as it is possible. They also added that for now, journalists haven’t experienced any interference in their work, but if it does come to outside pressure, they will make sure a Government takeover won’t go smoothly.

What happened?

On Monday, 17 September it was announced that Zoltán Spéder (one of Hungary’s so-called “oligarchs” who, for still-unclarified reasons, fell out of Orbán’s favour in 2016) has sold his media group, cemp-X Online Zrt., to board member Gábor Ziegler and entrepreneur József Oltyán. The latter is a member of the Christian Democratic People’s Party, a satellite party of the governing Fidesz, who, according to news reports has several times voiced pejorative opinions about Index.hu. This media group not only owns a number of online outlets, but also has the exclusive right to manage the advertising sales of Index.hu, whereby it has a direct effect on the operating revenues of the site.

The news site itself is still owned by the “For Hungarian Development Foundation” established by Lajos Simicska, an ally-turned-enemy of Orbán who was hoping that entrusting an independent foundation with the management of the website would allow its journalists to operate without pressure from any outside force – including himself. However, following the election victory of Orbán in April 2018, Simicska didn’t see any point in running his media empire anymore: Previously, he might have thought that letting journalists do quality work without interference would, to some extent, further his own goals as well (meaning that it would weaken the current government and thereby strengthen the positions of the political forces closer to his heart), but after the election night of 8 April, which brought a third 2/3rd majority in a row for Orbán, it became clear to Simicska that financing the severe losses of this media portfolio cannot be turned into political gains in a media landscape where the majority of media outlets is directly controlled by the Government (we have dealt with Simicska’s media holdings in an earlier article).

Even this independent foundation has become tainted: The “For Hungarian Development Foundation” was established by one of Simicska’s companies called Nanga Parbat Kft., which is now owned by the same pair of investors who also bought the above mentioned cemp-X media holding. This gives the new investors the right to change the leadership of the foundation. If they decide to do so, that will mark the beginning of the end for Index. While in the meantime the journalists have to cope with the fact that the Government’s people can attack from two sides: They either withdraw their money, or they can remove their bosses – neither is a good scenario.

Support from the masses

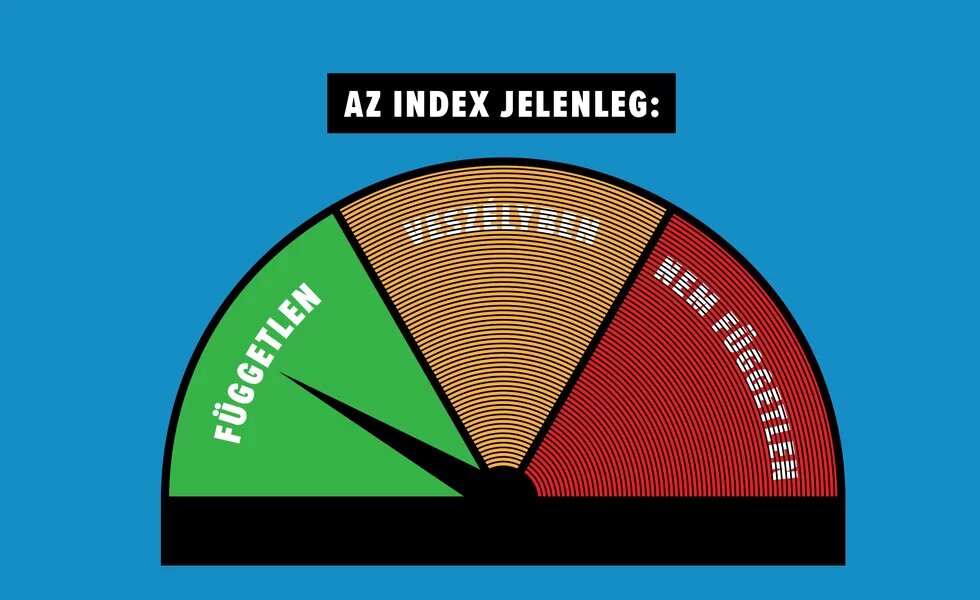

Such a delicate situation requires an immediate response from those affected; therefore, the journalists of Index have set up a new website called Szabad Index (meaning “Free Index”) which features an indicator that shows how independent their news site is. It can display three values: “independent”, “in danger”, and “not independent” – for now it is still in the green, independent zone, and there are hopes that it will stay so for quite some time. According to the editor-in-chief, the Index team has years of experience resisting outside interference, while Szabó adds that the government takeover would be a “noisy” manoeuvre involving the removal of at least two key persons from Index’s leadership – while the owners would probably want to avoid an obvious scandal. This should mean there is at least some time for the journalists to prepare for hard times.

Index has already started a crowdfunding campaign as part of which the newsroom managed to raise close to EUR 300,000 in the first month. This money should allow them to do reports and investigation, as well as continue acting as checks on the Government, even if cemp-X decided to withhold money from the company.

The amount collected in such a short timespan by Index is without precedent in the Hungarian media, where crowdfunding has been practiced for more than half a decade. Non-profit investigative news sites, such as Atlatszo.hu and Direkt36, as well as alternative media like Merce.hu are relying on donations from the audience to cover a large part of their costs (for Merce this is basically the only source of revenue), and in the last years even for-profit outlets like 444.hu and HVG started relying on the goodwill of their readers, as advertising revenues started to dwindle (in part due to the attractiveness of targeted ads on social media, and due to the Government’s growing influence on the media market). While there were initial fears that the crowdfunding pie could not increase as quickly as the number of media outlets that are hoping to get a slice, the experiences of independent news outlets give us grounds for optimism: From year to year each news outlet has managed to increase the amount of its donations.

However, in the case of a mammoth outlet like Index, it is still questionable what is going to happen in the longer run, as there must be a reason why Government-friendly entrepreneurs have gotten their hands on Index – and if they have a plan, its fulfilment can be prolonged, but it most likely cannot be stopped. Whether they want to close it, reshuffle it, or just turn it into “his majesty’s opposition” is all the same for the journalists working there: Most of them would not want to give their names and faces to an Index.hu different from what they have come to know during its 19 years of operations. What if they leave the sinking ship, though? Can the journalists continue their work without the 19-year-old brand? Editor-in-chief Attila Tóth-Szenesi said in the above-mentioned interview that it would be highly unlikely that the team of Index could set up a new outlet of the same size, once its death sentence has been pronounced by the owners. The experience of those media that were shut down under Orbán’s Government shows that newly-formed newsrooms start with a handful of journalists and almost no chance of finding investors in the Hungarian media market, so their chances of growth are quite limited. The two successors to the previous edition of the Origo.hu newsroom, Direkt36 and Abcug.hu, both operate with less than 10 journalists, while the founders of Magyar Hang had to make hard decisions about which journalists they could take over from Magyar Nemzet.

So even if there are positive signs, it is questionable in what form Hungary’s biggest independent news site (or at least its spirit and mission) can survive. With that we might be losing more than just another independent media outlet: Index is the last big news media outlet that was read by both supporters and critics of Orbán alike. If it ceases to exist in this form, it will further increase the gap between the parallel realities perceived by different parts of Hungarian society.

A chain of events

Index wouldn’t be the first casualty of 2018. This year the Hungarian audience has already lost five independent news outlets: The 80-year-old Magyar Nemzet was shot down right after the election, and soon the news broadcaster Inforádio, the English-language news site Budapest Beacon, and the conservative weekly Heti Válasz followed suit, while the news television station Hír TV was sold and turned into a government mouthpiece. Four of these outlets were owned by Lajos Simicska.

This transformation of the media landscape was followed by a purge in and around Hungarian academia. The editors of the conservative journals Századvég and Kommentár were forced to resign because some essays and studies were critical of the policies of the Government, the latest Századvég issue was removed from the website by the foundation publishing it, and both publications are expected to continue their operations as propagandists of the Government. In early October, the Hungarian Academy of Sciences cancelled two lectures: One was related to the demonised field of “gender”, which the Government has since removed from the list of accredited courses (the lecture looked at male and female roles and careers in the IT sector), while the other lecture was seen as too political (it was titled “The legal side of social media”). Finally, the news site HVG.hu reported that the Hungarian Government plans to privatise all universities in the country which, according to the “green” party (LMP) members would “increase tuition fees and force one-third of students from higher education,” not to mention that in a system in which Government funds will be even scarcer than today, only departments and universities sympathetic towards the government can hope for assistance, while those who encourage critical thinking will be left out in the cold.

All in all, the outlook for critical thinking and knowledge production, be it through the media or academic institutions, has become even a bit grimmer than it was before. Plurality of voices is further decreasing, access to information and knowledge is made even harder, while those working in the press or in academia have limited resources to fight back. The light at the end of the tunnel is too far away to see, while the Hungarian Government seems determined to go on until it completely redraws Hungarian society and its institutions.